The Mystery of Neuton's Tomb

Sarah Brown (University of York)

Compared to the monuments of Canterbury Cathedral, those of York Minster have fared badly and consequently have featured relatively little in the study of English medieval funerary commemoration. Some, including the spectacular bronze tomb of Dean William Langton (d.1279) were lost during the Civil War (1). The repaving of the cathedral 1731-8 and the fires of 1829 (choir) and 1840 (nave) both took their toll. As a consequence, many of the most important figures in the Minster's history no longer have surviving memorials in the building and in some cases even the location and the nature of their commemoration remains an open question. Treasurer John Neuton (1393-1414), one of the Minster's wealthiest canons, now remembered principally as the founder of the late medieval Cathedral library, appears to be strangely absent from the building in which he served. However in 1987 in an unpublished doctoral thesis, refined and developed in print in 2002, Dr Pamela King suggested that the cadaver tomb long associated, incorrectly, with Treasurer Thomas Haxey (1418-1425), now in the west aisle of the north transept (Figs 1 and 2), might be that of John Neuton, an attribution that deserves serious consideration (2).

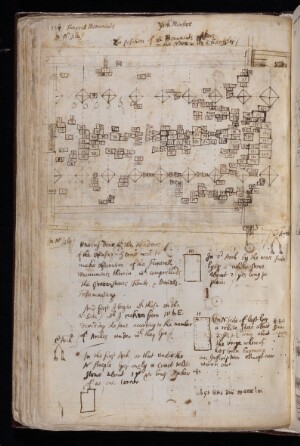

Critical to our understanding of Minster memorials is the manuscript of York antiquary James Torre (1649-1699) who made a careful record of many of the monuments and memorials to have survived into the last decade of the seventeenth century, listing them, with comment, and locating them on annotated plans (3). Not only did Torre record monuments that were subsequently destroyed, but his plans reveal some fascinating patterns of commemoration that are no longer preserved in the material record. For our purposes, the evidence for a concentration of memorials to the treasurers of York Minster at the east end of the nave is especially interesting (Fig. 3). Of the eighteen men who served in this post between 1360 and 1538, thirteen died in office and were buried in York (4). Torre helps us to identify memorials to at least eight of them at the east end of the nave, close to the first burial place and shrine of St William of York, archbishop until his death in 1154, but treasurer of the Minster from at least 1114 (5). Two treasurers, Richard Pittes (1414-1415) and Robert Wolveden (1426-1432), preferred burial in the new eastern arm (6). Hugh Trotter (1494-1503) requested burial 'where it shall please God', although his will makes it clear that he hoped to be buried close to Archbishop Rotherham, i.e. in the Lady Chapel (7). The burial locations of Thomas Portington (1477-1485) and Robert Langton (1509-1514) are unrecorded. Treasurer John Neuton had not, it would seem, preordained his tomb, but had specified its location, asking for his body to be given ad sepeliendum in ecclesia Eboracensi, juxta predecessores meos ('to be buried in the church of York, next to my predecessors'), clearly placing his last resting place with the majority of his fellow treasurers at the east end of the nave (8). The very Thomas Haxey with whom the cadaver tomb has been associated, was, together with William Waltham, archdeacon of the East Riding, and John Gylby, rector of Kneshall, one of Neuton's three executors and by far the most influential of the three in the Minster—a man who could be trusted to carry out Neuton's wishes and ensure the perpetuation of his memory in the Minster. Haxey was also to be closely involved in the construction of the new library into which Neuton's bequest of books was deposited.

Antiquary Henry Johnson, writing in the 1670s, seems to have been the first to associate the cadaver tomb with the name of Thomas Haxey (9). This (mis)attribution was repeated by Francis Drake in his magisterial volume Eboracum published in 1736, just as the repaving of the nave was resulting in the moving of the monument from its position to the right of the north-west crossing pier to its current location (10). Given Drake's reliance upon Torre for so many other facts, this is a strange error to perpetuate, but is suggestive of an entrenched oral tradition in connection with the battered monument and the uses to which its stone top were put. Thereafter this attribution to Haxey received almost universal acceptance (11). It is to Torre that we must turn for the correct identification of Haxey's monument, a slab with indented brass, labelled as 149 on his plan:

[In the margin] Thomas Haxey, 1424.

On N. side of last [monument number 148] lyes a blue marble about 5 y[ar]ds long, w[hi]ch has been escocheoned at corners, & on a plate at the head bears this inscription viz + hic iacet Thomas de haxey quondam Thesaurari[us] huius Eccle[sie], qui obiit xxi die men[sis] Jan[uarii], an[n]o do[mi]ni Mccccxxiiii cuius an[im]a p[ro]p[itie]tur deus Amen (12).

Although by c.1690 lacking any identifying inscription, the battered cadaver effigy and its enclosure were also described in some detail by Torre, who labelled the monument on his plan as number 150 and recorded it in its original east-west orientation, to the south of the north-west crossing pier:

On N. side of last [i.e. number 149, the monument of Thomas Haxey] by the N.W. Lanthorn-pillar, lyes an old monument cutt into the Effigies of a man in his winding sheet & raised in solid white stone inclosed on both sides & at the head with iron grates about a y[ar]d high, W[hic]h support an Altar stone of black Marble about 3 y[ar]ds long (& it is commonly mistaken for haxey tomb by it & called Haxby tomb) (13).

There can be little doubt, therefore, that the cadaver tomb was not that of Thomas Haxey, a fact confirmed by the location of the ledger slab of William Fenton, former rector of Nether Wallop (number 139 on Torre's plan), who requested burial next to the body of his former master Thomas Haxey. Fenton's slab touched memorial number 149, but not number 150 (14).

Pamela King offered a theory as to how the cadaver tomb came to be associated, wrongly, with the name of Treasurer Haxey. Most importantly, it lay close by the north-west crossing pier that had been repaired c.1409 under his supervision, following the collapse of the central tower (15). She went on to suggest that the cadaver tomb was, in fact, that of Neuton, a hypothesis that relies heavily on its association with Haxey. She argued that oversight by Thomas Haxey and his fellow executors of the creation of this distinctive and novel monument in Neuton's memory, the only example of a cadaver tomb in the Minster, and its proximity to a structure already associated with Haxey's name, accounts for the mistaken attribution. She demonstrated, very effectively, that the scholarly cultural milieu to which these men all belonged would make them receptive to the new style of cadaver monument, even though Haxey himself subsequently commissioned the more conservative slab-with-brass model.

King's hypothesis has much to commend it, not least that her attribution of the cadaver to Neuton would make the York monument the earliest example of its kind in England. However, another monument must be considered as Neuton's, and one which accords far more closely with the one recorded expression of his intentions for his own burial, namely that he be interred next to his predecessors. The cadaver tomb was originally located next to one of Neuton's successors and is actually separated from his predecessors. It cannot be described therefore as being next to Neuton's immediate predecessors, as his will implied. Thanks to Torre their burial places can be identified, located in a row under a series of blue stones of similar size, immediately to the east of the tomb-shrine of St William (in other words at the feet of St William, their illustrious and sanctified predecessor in the office). The cadaver monument, number 150 is also set slightly to the west of this line, if Torre's plan is to be trusted. Reading the identities from south to north (right to left on Torre's annotated plan), the treasurers' monuments are as follows:

North |

|

|

|

| South |

| 149 | 148 | 147 | 146> | 145 | 144 |

| Thomas Haxey (1418-1425) | Unidentified by Torre | John de Clifford (1375-1393) | John Berningham (1432-1457) | John de Branketre (1360-1375) | John de Nottingham (1415-1418) |

| Arms (in glass in choir and library): Argent three buckles in fess sable | Arms on the monument recorded by Torre: '6 falcons heads erased' | Arms on the monument recorded by Torre: 'Checky on a fess three leopards faces' |

|

| Arms on the monument recorded by Torre: 'An orle + 3 Annuletts in chief' |

Looking at Torre's plan, one is immediately struck by the monuments' consistency of size and type. All were flat and contained brass indents, and several retained shields of arms, recorded by Torre and a number of his fellow antiquaries. They were consequently very similar to the arrangement of blue stones covering the burials of archbishops of York arranged in a row before the Lady Chapel altar at the behest of Archbishop Thoresby. Monument 148, which fits Neuton's burial request perfectly, being sited immediately adjacent to the tomb of his immediate predecessor John de Clifford, was described thus by Torre:

'On the N side last [i.e. monument 147, of John de Clifford] lys another blue stone of the same bigness escocheoned at the corners thus [drawing of a shield] viz 6 falcons heads erased and at the head was a square plate' (16).

These same arms were found in at least two other locations in the Minster. In a window on the south side of the library Torre recorded the arms 'B[lue] 6 falcons heads erased O[r]' and labelled his drawing of the shield 'Fenton' (17). He saw the same shield at the base of the fifth light of choir clerestory window SVIII, part of the glazing campaign of c. 1408-1414, locating it to the right of a shield of Clifford (in the fourth light) (18). Four other antiquaries (Robert Glover in 1584-5, Roger Dodsworth in the 1620s, Matthew Hutton in 1661 and Henry Johnson in 1670) recorded the same shield, although Hutton called the birds hawks rather than falcons (19). Dodsworth, Hutton and Johnson agree with Torre in placing the shield in the fifth light of SVIII, with the arms of Clifford in the fourth (20). According to Glover and Dodsworth, the shield was accompanied there by an inscription: 'Magister Johannes Fenton, legum doctor, qui obiit MCCCCXIV'. Torre's attribution of the arms in SVIII to 'Fenton Joh obiit 1414' is abbreviated and in smaller letters, in a lighter ink, than his main description of the window and looks like a marginal addition. As he is known to have used Dodsworth's notes it is possible that he took his 'Fenton' attribution from this source. Glover and Dodsworth describe the ground of the shield as green, while Hutton and Johnson agree with Torre's description of gold charges on a blue ground. John Browne recorded the same shield, with a blue ground, in window SVIII, although by the 1850s the shield had moved from the fifth light to the first (where it can be seen today, Fig. 4), and the inscription had disappeared, probably as a consequence of the 1829 fire, which had resulted in the damage and repair of many of the shields (21). The Clifford arms have remained in the fourth light.

No record can be found of a Master John Fenton, doctor of laws, who died in 1414 and who might have deserved a memorial in a window in the south choir clerestory, in the glazing of the library and on a large monument at the east end of the nave, next to the tomb-shrine of St William and five Minster treasurers. However, allowing for a possible mis-transcription of the first three letters of a surname read from a considerable distance, this identity and date of death would perfectly fit Treasurer John Neuton, active in the promotion of the rebuilding of the Minster choir in this period and donor of a major bequest to the library (22). This hypothesis would place him in death next to his predecessor, John Clifford, as his will requested, a relationship that was also, apparently, borne out in the arrangement of shields in clerestory window SVIII.

The shield of six falcons' heads erased (i.e. cut off at the neck, with a jagged edge), is an unusual one and the medieval ordinary does not assist in its identification. Neuton, thought to be the son of a York mercer of the same name is unlikely to have been personally armigerous, but it is clear that a number of his predecessors in the post of treasurer and several of his contemporaries in the chapter did bear arms, while the decoration of the choir clerestory in glass and stone attributed fictive arms to a number of historic figures (23). If the charges on the putative Neuton arms are read as eagles' heads rather than those of a falcon, the charges could be read as an oblique reference to the Evangelist symbol of Neuton's name saint, St John (24). Other punning uses of the eagle by clerics named John, albeit of later date, can be cited, including John Wheathamstead, Abbot of St Albans (1421-1460) and John Cantlow, Prior of Bath (1489-1499) (25).

Neuton was buried in sight of the carving of the horn and arms of Ulph, in the first north bay of the nave arcade (Fig. 5). One of the Minster's most treasured possessions, the horn was carved onto the arcade of both the nave and the new Lady Chapel, in the first bay on the north side in both cases, accompanied by Ulph's coat of arms (vert, six lioncels or) and both are also depicted in the south choir arcade. They are also found with the royal arms on the interior of the west wall of the nave. As Treasurer, Neuton was entrusted with the custody and care of this enigmatic item. It is an oliphant of late eleventh-century date and has long been associated with the gift of lands to the Minster by the Danish nobleman Ulph Thoroldsson, a grant confirmed by Edward the Confessor (26). The carvings in the nave attest to the continuity and longevity of this tradition, although the earliest documentary mention of it is found in the metrical chronicle composed during the archiepiscopacy of Thomas Arundel (1388-1397), suggesting a renewed interest in the antiquity and symbolism of this object in those circles of which Neuton was a prominent member (27). Neuton himself had paid for a new mount (zona annexa) to be added to the horn (28). It has been suggested that this was in the form of a silver mount which was probably lost when the horn was stolen in the seventeenth century (29). In fact, the term must surely refer to a strap rather than a metal band around the horn, and it is therefore of considerable interest that in the nearby carving of the horn in the spandrel of the south choir arcade (under window SIX), the horn is shown on a far larger scale than the horn in the nave, suspended from a thick strap that is quite different from the earlier version depicted in the nave (Fig. 6). It is also surely no accident, that Ulph, holding his horn, is prominently depicted in one of the tracery lights of choir clerestory window SVIII (Fig. 7) (30).

While this re-examination of the evidence for a monument to John Neuton in York Minster may leave the identity of the cadaver effigy once more open to question, through the discussion of an accumulation of circumstantial evidence, it places his interment in the midst of his fellow office-holders, and at the feet of St William. It also suggests that Neuton was (and still is!) remembered in the glazing at the very liturgical heart of his cathedral, as well as in the library building created as a response to his extraordinary donation.

(1) S. Badham, 'A lost bronze effigy of 1279 from York Minster', Antiquaries Journal 60 (1980), pp. 59-65.

(2) P. M. King, 'Contexts of the Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth-Century England', unpublished DPhil thesis, University of York, 1987, appendix 2, pp. 494-498; P. M. King, 'The treasurer's cadaver in York Minster in York Minster reconsidered' in The Church and Learning in Late Medieval Society. Studies in Honour of Professor R.B. Dobson/Harlaxton Medieval Studies XI, ed. by C. Barron and J. Stratford (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2002), pp. 169-209. A cadaver tomb is one in which the effigy of the deceased is depicted as an emaciated cadaver wrapped in a shroud, rather than as a figure in repose, dressed as in life.

(3) York Minster, Archives of the Chapter of York, L1 (7) (James Torre, ‘Antiquities of York Minster…’), fol. 75v.

(4) Three men left York to take up other posts. Treasurer Robert Gilbert (1425-1426) became dean in 1426 and left York in 1436 to become bishop of London and is unlikely to have been buried in York; John Booth (1457-1459) was made bishop of Exeter and was buried in London; William Sheffield (1485-1494) left York to become Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield and was buried in Lichfield cathedral.

(5) Torre (York Minster, Archives of the Chapter of York, L1 (7), fols 95r-96v) identified the memorials of Treasurers John de Branketree (1360-1375), John de Clifford (1375-1393), John de Nottingham (1415-1418), Thomas Haxey (1418-25), John Bermingham (1432-1457), John Pakenham (1459-1477), Martin Colyns (1503-1509) and Lancelot Colyns (1514-1538); here Torre quoted Dodsworth, who had seen his brass before its loss during the Civil War in the vicinity of St William's tomb-shrine at the east end of the nave.

(6) Richard Pittes requested burial close to his patron, Archbishop Henry Bowet, whose monument stands between the Lady Chapel and All Saints Chapel; Robert Wolveden requested burial in the new work 'about the porch before the altar of the Virgin'.

(7) Testamenta Eboracensia..., ed. by J. Raine, Surtees Society 53, IV (London: Nichols, 1869), pp. 219-220.

(8) Testamenta Eboracensia..., ed. by J. Raine, Surtees Society 4, I (London: Nichols, 1836), p. 365. See also The Latin Project, The Testamentary Circle of Thomas de Dalby, Archdeacon of Richmond, d.1400 (York: The Latin Project, 2002), pp. 66-74.

(9) Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Top. Yorks. c 14 (Henry Johnson's Notebooks), fol. 25/42.

(10) F. Drake, Eboracum or the History and Antiquities of the City of York (London: William Boyer, 1736), p. 501.

(11) The notable exception is James Raine, who in The Fabric Rolls of York Minster, Surtees Society 35 (Durham: George Andrews, 1859) p. 206, was aware of Drake's error in attributing the cadaver tomb to Haxey.

(12) York Minster, Archives of the Chapter of York, L1 (7), fol. 96r-v.

(13) York Minster, Archives of the Chapter of York, L1 (7), fol. 96v.

(14) Nether Wallop had been granted in perpetuity to York Minster by Henry I, having been part of the southern estates of Herbert the Chamberlain, father of William Fitzherbert (St William). It was in the hands of William the treasurer by 1133. C. Norton, St William of York (York: York Medieval Press, 2006), pp 10, 47-48, 228. It remained in the patronage of the Treasurer until 1459, when it passed to the vicars choral of York. The Cartulary of the Treasurer of York Minster and related documents, ed. by J. E. Burton (York: Borthwick Institute of Historical Research, 1978), p. viii.

(15) S. Brown, 'Our Magnificent Fabrick'. York Minster: An Architectural History c.1220-1500 (Swindon: English Heritage, 2003), pp. 195-197.

(16) York Minster, Archives of the Chapter of York, L1 (7), fol. 96r.

(17) York Minster, Archives of the Chapter of York, L1 (7), fol. 74r.

(18) York Minster, Archives of the Chapter of York, L1 (7), fol. 61v.

(19) The Visitation of Yorkshire made in the years 1584/5 by Robert Glover Somerset Herald etc, ed. by J. Foster (London: Privately printed, 1875), p. 430, no. 84; London, British Library, Harley MS 6984, fols 56v-62r; Oxford, Bodleian Library, Dodsworth MS 137, fol. 17r; Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Top. Yorks. c 14, fol. 46.

(20) The numbering of the windows follows the Corpus Vitrearum notation.

(21) J. Browne, A description of the Representations and Arms on the Glass in the Windows of York Minster, also the Arms on Stone 1859 (Leeds: Richard Jackson, 1917), p. 241. Today, only three of the falcon heads are medieval and the background blue glass is fragmented and much of it is nineteenth century.

(22) I am grateful to my friends and colleagues Professor Claire Cross, Ann Rycraft and especially Professor Christopher Norton for discussing this matter with me.

(23) Shields of arms can be securely attributed to treasurers John de Clifford, John de Nottingham, Thomas Haxey, Robert Wolvedon, John Pakenham and Martin Colyns.

(24) By the seventeenth century, when the 'Fenton' arms were recorded, the visual distinctions between eagles and falcons would have been clear. In the early fifteenth century, this distinction is likely to have been less clearly defined. This is acknowledged in Michael Powell Siddons' study of heraldic badges, in which he says of the falcon 'Except where a falcon is portrayed belled, or where there is a punning reason for seeing one rather than the other, it is often very difficult to tell whether a bird is an eagle or a falcon' (M. P. Siddons, Heraldic Badges of England and Wales, II (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2009), II, p. 98). The characteristic of the eagle is its open beak, often with the tongue displayed, and the upstanding feathers on its neck. The falcon, in contrast, has a closed beak and smoother feathers. The fifteenth-century birds in the shield in window SVIII have been heavily re-leaded, but some of the feathers on the neck do seem to angle away from the neck. The beak is open. I am grateful to Philip Lankester for discussing this issue with me with characteristic generosity.

(25) M. P. Siddons, Heraldic Badges of England and Wales, I (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2009), p. 17.

(26) T. D. Kendrick, 'The horn of Ulph', Antiquity 11 (1936), pp. 278-282.

(27) J. Raine, The Historians of the Church of York and its Archbishops, II (London: Longman, Rolls Series 71, 1886), p. 456.

(28) J. Raine, The Historians of the Church of York and its Archbishops, III (London: Longman, Rolls Series 71, 1894), p. 386.

(29) The present silver mount and chain, with inscription recording the theft, was made in 1675 at the behest of Henry, Lord Fairfax. Kendrick, 'Horn of Ulph', p. 278.

(30) The possible significance of this image for the identity of heraldry depicted in window SVIII was first discussed by the late Tom French in a posthumously published article, 'A mystery shield in York Minster', Friends of York Minster Annual Report 72 (2001), pp. 35-39. In attributing a heavily restored shield in panel 2b (argent on a bend sable cotised or a saltire engrailed or) to Dean John Prophete, French suggested that Neuton's arms had once been located in panel 2c, under the image of Ulph, and were therefore those already lost by the time the seventeenth-century antiquaries saw the window.

How to cite

Sarah Brown, 'The Mystery of Neuton's Tomb', in Hanna Vorholt and Peter Young (eds), 1414: John Neuton and the Re-Foundation of York Minster Library, June 2014, https://yml1414.york.ac.uk/